Soultime Mood Checker

How developing our Emotional, Social and Spiritual Intelligence (ESSI) can improve understanding of our innermost beliefs

This is a short explanation and description of the background to the Mood Checker. It briefly explains why learning to accurately observe, name, record and reflect on our emotions, their causes and their consequences, can lead to a better understanding of our innermost beliefs. And why a clear understanding of our innermost beliefs is a prerequisite to being able to let go of the false beliefs that hurt us and embrace true ones that allow us to experience more positive emotions and express them in changed actions.

Introduction to the Soultime Mood Checker

The purpose then of the Mood Checker is to encourage and help people to regularly and accurately observe their emotions in all three dimensions - with themselves, with others with God. The careful observation of the emotional country we are passing through enables us to navigate it better. When we start to recognise features of the landscape we begin to know where we are and possibly to gain insight into how we might get from where we are to where we want to be.

The Mood Checker’s built-in journal is designed to encourage reflection on the reasons behind particular emotions. Why do I feel what I’m feeling? How did I come to this place? This kind of reflection can help begin to identify unhelpful inner beliefs which is the first stage in modifying them.

Background

The role and nature of emotion has long been controversial. As discussed in more detail below, some see emotions as troublesome and to be controlled, others as important and to be paid attention to. What nobody denies is that they have a significant influence on our behaviour. Whether we like it or not, our everyday actions largely flow from our emotional responses to our encounters with other people and the circumstances of our lives. The table below illustrates:

| Circumstance | Emotion | Action |

| Meet someone | We like them | We’re pleasant to them |

| Meet someone | We dislike them | We avoid them |

| Someone insults us | We’re hurt | We are angry with them |

| Someone ridicules us | We’re ashamed | We hide |

| We fail at a task | We feel hopeless | We lose motivation |

So routine is our understanding of this connection between emotion and action that we regularly run the tape backwards, inferring people’s emotions from their actions. We see someone slam a door after a conversation, we infer that they are angry.

Everyone is concerned about their personal actions but people have very different accounts of how good and well regulated personal actions come about and how to account for the emotional component of our actions.

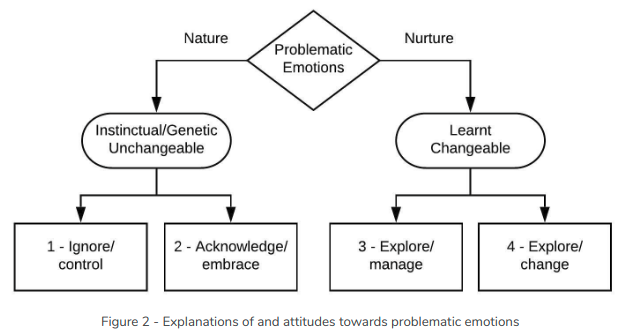

For the purposes of this discussion we will distinguish two main accounts of how emotions impact our actions. Simplistically, either “nature” or “nurture”. Both views acknowledge the power of emotions on our actions but each offers a very different accounts of the origin, value of and prescriptions for handling problematic emotions. Though this “nature” or “nurture” distinction is rarely thought of as being absolute; it is usually a matter of emphasis of one over the other. Nonetheless, distinguishing these two accounts can provide a useful basis for discussion.

The “nature” point of view is essentially that problematic emotions are either impossible, or at least extremely difficult, to change. This viewpoint tends to see emotions as part of our genetic, or at least inherent make up. In a Christian account they can sometimes be seen as part of an intractable fallen nature. However, within this viewpoint the prescriptions of what to do about intractable emotional responses can be sharply contrasting.

For one group (1) it follows that if difficult emotions are impervious to change or management, because they are so unruly and disruptive, they must either be ruled over, or they will rule over us. In this account, for a person to live a good life, difficult emotions must be denied and/or controlled. The denial and control approach can be found in the ancient world, in popular culture it is now often associated with “Victorian” religious morality but even in the 1940’s it was suggested that the IQ test should include questions that scored positive when people did not become angry, grieved, fearful, inquisitive etc.2

The other group (2), who also see emotions as intractable, doubt whether emotional responses can ever really be controlled or contained. In their view, however much actions are apparently controlled, emotional responses always “leak” out. Outward control simply leads to denial of true feelings - to “repression” and to hypocrisy. This picture in modern culture is largely associated with Freud and modern psychology. This “accept and embrace” approach is probably most frequently associated with the sexual revolution of the ‘60’s.

1Animo imperato ne tibi animus imperet. Rule your feelings lest your feelings rule you. Sententiae, Publilius, Syrus, 1st cent. B.C

2Woodworth, R., 1940. Psychology. 4th ed. New York: Henry Holt & Company.

The “nurture” account of our emotional responses, by contrast, tends to see emotional responses as being less immutable; as being less genetic or inherent and more learnt from our upbringing and life experience. It sees emotional responses as largely the result of the interaction of social and life experiences with each individual's inner beliefs - which are in turn often held below the level of everyday consciousness. The figure below illustrates.

As a simple example, when we believe people don’t fundamentally like us, social interaction results in anxiety and a withdrawal from others. Or again, when we believe we are fundamentally of value we feel confident and approach life with purpose.

Because these kinds of inner beliefs are help subconsciously, many deny their influence or even existence. However, experimental work on infant attachment has now clearly and measurably demonstrated that the inner beliefs formed in our earliest years about how others will treat us that have long term effects on our emotions, and hence our behaviours3.

From this “nurture” viewpoint even the most problematic emotional responses can be seen as in some ways valuable. They tell us something important about ourselves and can, with care, be understood, managed and even modified. This viewpoint then sees the acknowledgement, and deeper understanding, of emotional responses as being the first stage in the management of, and possible change to, our emotional responses.

Of those that see emotional responses as valuable there are some that emphasise the management, more than the change, of our emotional responses. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) would be the most common example of this approach. Talking and psychotherapeutic therapies, on the other hand, are based on the idea that the emotional responses can themselves be changed if the original, often subconscious, learnings about life can be modified.

Emotional, Social and Spiritual Intelligence (ESSI)

During the course of the 20th century IQ tests became popular but as time went on it became increasingly apparent there were aspects of cognitive ability IQ tests did not fully explain. By the 1980’s additional kinds of intelligence were being proposed such as Emotional Intelligence (EI) that looked at a person’s capacity to understand themselves and to appreciate their own feelings, fears and motivations. Also Social Intelligence (SI) which looks at a person’s capacity to understand their own feelings, fears and motivations in relation to others and, as a result, other people’s intentions, motivations and desires towards them. .

EI in particular entered mainstream discourse and brought to a wider audience a greater focus on how if we want to regulate our actions, we need to first become aware of the emotions that are propelling them. This recognition of the importance of becoming aware of emotions in turn interacted with the growing mindfulness movement.

What we are now proposing is that a third intelligence be added to the list, Spiritual Intelligence (SI) - looking at a person’s capacity to understand their own feelings, fears and motivations in relation to God so that as a result they gain a better understanding God’s intentions, motivations and desires towards them.

3 I Bretherton, Developmental Psychology 1992, \fol. 28, No. 5,759-775

4Salovey, P. & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185-211.

5Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind. New York: Basic Books

Jesus himself points us to this three dimensional view of “intelligence” when he commands us to “love the Lord… and to love our neighbours as ourselves”. It is useful to distinguish emotions related to ourselves, those that relate to other people and those that relate to God.

In one sense there is nothing new in this. When Peter, the disciple, tries to persuade Jesus that dying on the cross was a bad idea, Jesus famously rebukes him be saying “get behind me Satan”6. Peter did not yet understand God’s intentions, motivations and desires. But as emerges later, in the story of Peter’s denial of Jesus, it is Peter’s very lack of understanding of himself and his inner beliefs about God that is at the core of Peter’s own lack of understanding of God’s intentions. Peter did not have an inner belief in God the Father’s overarching power and protection. As Peter begins to understand his own heart beliefs better, he in turn comes to understand God.

Our proposal is that as we become more aware of our own feelings towards God and so illuminate our own inner beliefs, we can, as Peter did, adjust our inner beliefs and as a result gain a truer understanding of God’s intentions, motivations and desires.

It may be objected that emotions related to God are irrelevant to those that don’t believe in God. However, even people that don’t believe in God often say things like “the world is against me”, or “I’m just unlucky” and so forth. Our contention is that everyone has deep underlying attitudes and emotions related to “life” or “the universe”. These attitudes and beliefs are often overlooked. That even for those that don’t believe in God, it’s vital to understand and deal with this important dimension of our emotional background and decision making.

6 Matthew 16:23

Growth in Emotional, Social and Spiritual Intelligence

Being able to accurately observe and name our emotions is the vital first step before we can begin to properly regulate our emotions. It is surprising then that in the modern world it is common for people to be unable to accurately name the emotions that they are currently feeling.

Many of us spend a great deal of effort trying to control our outward actions but often give little time trying to understand or regulate our underlying emotions. Unfortunately this approach can have negative consequences. We’ve all seen people trying to control their actions without understanding the emotions that are driving them - someone who’s angry but says they’re not, someone who is in love but denies it. This kind of behaviour, rather than improving regulation, tends to gradually lessen our ability to regulate ourselves because it hides the mechanics of regulation from us.

In every sphere of life proper regulation cannot exist without observation and measurement coming first. So if we want to regulate our emotions, and hence the actions that flow from them, we first have to be able to accurately observe and measure them. Measurement and regulation are two sides of the same coin. If someone can’t estimate what is fast, as opposed to slow, nothing happens when you say “slow down”. If someone can’t read the time there’s no point say “don’t be late”.

The connection between measurement and regulation is as close in physics and mechanics as it is in group behaviour or emotional regulation. When we measure anything we do something profound. We move from the world of senses to the world of semantics. We cross an epistemic bridge. We move from the world of mere reaction to the world of regulation. From being powerless, to being powerful people.